Howard might not have come across as such a calm person in late 2005, when he found out he was HIV-positive. After his diagnosis, he felt "dirty" in his own skin, and feared infecting others if he so much as cut his hand. Getting the wrist tattoos helped him in his journey toward self-acceptance.

"It's a branding of who I am, and it's a branding of being comfortable with that, being comfortable with who I am," said Howard, 37, who lives in Portland, Oregon.

Howard is one of many people living with HIV who have chosen to get tattoos to represent living with the disease. They say these tattoos help start conversations, reduce stigma and serve as reminders of how living with HIV has changed their lives.

Tattoos like Howard's biohazard symbol are especially common in men who have sex with men, the subpopulation that bears the highest burden of new HIV infections in the United States. Men who have sex with men accounted for 61%, or 29,300, new HIV infections in 2009, federal health officials said last week. And although the number of new HIV cases has remained stable in the general population, new infections rose among young, black gay and bisexual men from 2006 to 2009.

It was also among men having sex with men that U.S. doctors first realized, in 1981, that there was a never-before-seen disease that could destroy the immune system. That disease came to be known as human immunodeficiency virus.

"In the gay male community, we think about it (HIV) a lot more because it attacked our community first. It's wiped out a number of us," said William Conley of Pollock Pines, California. His tattoo, a biohazard symbol with the Celtic motif of a crown of thorns circling around it, means he's winning the fight against this disease.

Gallery: Tattoos as symbols for HIV/AIDS

Gallery: Tattoos as symbols for HIV/AIDS RELATED TOPICS

- HIV and AIDS

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Tattooing and Body Modification

Identification and awareness

The origins of HIV-related tattoos are murky, but the biohazard symbol is recognized in connection with HIV among many gay men, said David Dempsey, clinical director at the Alexian Brothers Bonaventure House in Chicago and The Harbor in Waukegan, Illinois, both transitional living facilities for HIV-positive individuals recovering from alcohol and substance dependence.

"It's to let other men know that they're HIV-positive so that they don't have to come out and say it," he said. In situations of anonymous sex, it can signal status to potential partners and, in that sense, may help with prevention, because unprotected sex with an HIV-infected individual can spread the disease, he said.

For those with HIV, seeing someone else with a biohazard symbol is a sign this is another person living with the disease who might provide support, Conley said, like a "secret identification code."

There are less cryptic HIV tattoos, too. Dempsey has a red AIDS ribbon tattoo on his chest, which he chose even before he became HIV-positive (the organization Visual AIDS created the ribbon symbol in 1991). Dempsey has been a social worker in the HIV community for 11 years, and wanted to show solidarity with people living with the disease, as well as raise awareness.

In 1986, when AIDS was just starting to be recognized as a deadly illness transmitted through sex and intravenous drug use, conservative author William F. Buckley Jr. suggested HIV-positive people get tattoos to protect others. He wrote in The New York Times, "Everyone detected with AIDS should be tattooed in the upper forearm, to protect common-needle users, and on the buttocks, to prevent the victimization of other homosexuals."

Some HIV-positive individuals may have gotten tattoos in resistance to Buckley's article, said Richard Sawdon Smith, professor of photography and AIDS cultures at London South Bank University in the United Kingdom, who has been HIV-positive since 1994. This is not an oft-cited reason among people with tattoos today, although many of the people who got HIV in the '80s and may have gotten tattoos then have since died.

Another theory is that certain ACT UP activists sported biohazard tattoos in their massive demonstrations in the late '80s and early '90s, but founder Larry Kramer said he hasn't heard of these tattoos or of the organization's participation in the practice.

Tattooing HIV-related symbols has been going on at least since Nick Colella started at Chicago Tattooing and Piercing Company in 1994.

Colella used to tattoo more memorial motifs honoring people who had died of AIDS when he was starting out -- less so now, since modern antiretroviral medications effectively let patients live long lives with HIV as a chronic illness. Colella, like other tattoo artists, sterilizes his equipment and throws used needles away in biohazard-labeled containers so diseases transmitted through blood, including HIV, do not spread from person to person.

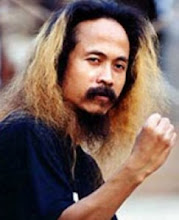

Showing the world his HIV-positive status through tattoos was like a second coming out for Michael Lee Howard.

"People symbolize happiness, sadness, sexuality, everything with tattoos. It's all the good, all the bad, all the everything," he said.

Some people get HIV-related tattoos immediately after getting a positive test result. Conley waited three days after his diagnosis in 2009 to get his tattoo.

Conley, a sociologist by training, knows of 45 to 60 others in online forums who have tattoos involving a biohazard symbol or a scorpion, another sign of having HIV in the gay community. The stinging tail of the scorpion alludes to the virus, he said.

"Basically saying, 'I'm positive and you need to know that, especially if we're going to engage in any intimate relation' -- it has that meaning," he said.

Coming to terms with diagnosis

Howard found out about the biohazard sign as a symbol for the HIV-positive gay community through the Internet. The radiation design, though, was his own idea. He chose it because in comic books, when superheroes get radiated, life "starts from scratch," he said.

That's what Howard felt like he needed: A rebirth. Getting HIV had been a total shock. He had briefly dated a man who said he didn't have sexually transmitted diseases, but later Howard found out the man was HIV-positive and had given him the virus. Before then, Howard didn't know anyone who was HIV-positive.

His diagnosis was a wake-up call to better his life. Deep down, he said, he wasn't a happy person and wasn't being his true self on his blog, which felt like "a Hello Kitty commercial" -- too perky for what he actually felt. He went into three years of intense therapy in an effort to find his "authentic self."

"I just got tired of being what everybody else wanted me to be," he said. "I think that's part of where the tattoos came in: I didn't get tattoos or as many piercings, because that's not what you do. You do what everyone tells you to do."

"After my diagnosis I'm like, 'Well hey, I have nothing left to lose.' "

Showing the world his status through the tattoos was like a second coming out for Howard. And the responses from others about the tattoos have been overwhelmingly positive. Since his tattoos are so prominent, Howard gets asked about them all the time. They give Howard opportunities for dialogue about living with HIV, with everyone from fellow light-rail commuters to his boss.

Talking about it

Opening up those kinds of conversations is why Chad Hendry, 32, got a bold tattoo from Colella in July. On his neck is a red AIDS ribbon with the words "On this day my new life began" and the date of his diagnosis: 12-30-09.

He's not sure whether he got HIV through sex or drugs; he knew his behavior was risky, but he never thought he'd get the disease. After about a year, though, his health declined, and a test showed he had HIV. Rehab helped him curb his crystal meth addiction, and his grandparents helped him get back on his feet. He lives in an HIV recovery home near Chicago.

A red HIV T-shirt campaign gave him the idea that he wanted a tattoo related to his status. People would see the shirt and ask questions about living with the virus; with a tattoo, Hendry could have that level of engagement all the time.

"It's the same reason I'm very vocal about it: because I believe that will make the path just a little bit easier for somebody else," he said.

But the tattoo hasn't entirely brought him comfort. Hendry fears he might not find a partner who is comfortable with the statement of the tattoo. His family members weren't entirely welcoming of it -- they wondered why it had to be so prominent on his neck. People on trains seem to stare at it, too.

Still, Hendry loves his tattoo. He's not ashamed of having HIV; in fact, he feels it's one of the best things that has happened to him, because he's off drugs and has a better outlook on life.

"Today I live every day with gratitude. You become grateful for what you have in being alive," he said.

The ribbon motif also appealed to Howard of Portland. To commemorate his five-year "posiversary" in November, he got a red ribbon tattoo on his shoulder with his diagnosis date.

"I think that I'm the most comfortable and happy in my own skin that I've ever been in my entire life," Howard said.

No comments:

Post a Comment